The season of ghost stories has arrived. Head to any major cinema complex this week, and you'll find at least three films revolving around ghosts, haunted spaces, and haunted minds. These films feature individuals from all walks of life, forced to confront their losses amid the malevolent spirits that haunt them. Despite the mounting toll these spirits take, these individuals engage with them, battling them on both a physical and emotional level. What is the hope? Survival? A deeper understanding of life and death? Or perhaps a calling that cannot be ignored?

Of course, we associate these elements with horror. But imagine if we approached these elements from a different perspective—one without horror, yet still inherently concerned with being haunted. The most surprising ghost story of the season isn't about terror; it's the story of one of America's greatest artists grappling with spirits and trying to contain them on a cassette, serving as its own kind of sacred vessel. In Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere, filmmaker Scott Cooper continues his work of exorcising America's soul.

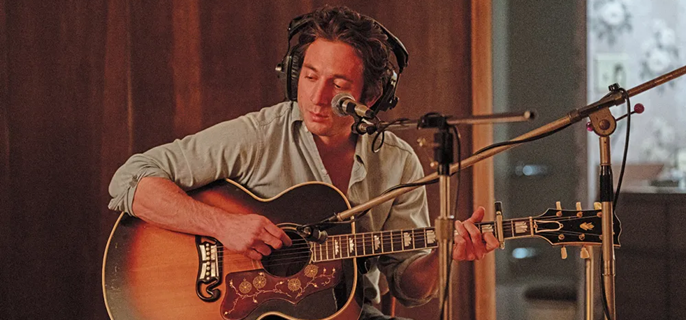

As many fans of Bruce Springsteen are aware, his sixth studio album, Nebraska (1982), marked a significant departure for the artist. Nebraska was his most personal album, featuring somber, stripped-down tracks recorded in solitude without the E Street Band. While retaining the blue-collar perspective that Springsteen had made his name on, Nebraska was forged from America's violent past, both real and fictional. Inspired by the killer Charles Starkweather, the short stories of Flannery O'Connor, Charles Laughton's The Night of the Hunter (1955), Terrance Malick's debut film Badlands (1973), and Springsteen's own emotionally fraught childhood, Nebraska's composition, recording, and release are chronicled in Warren Zanes' book Deliver Me from Nowhere (2023) and Springsteen's autobiography Born to Run (2016), which form the basis of Cooper's film and Jeremy Allen White's portrayal of the man.

Like the album Nebraska, Cooper takes an unconventional approach to Springsteen's story, making it one of the decade's most compelling biopics of an artist, entirely unconcerned with being a crowd-pleaser for the masses. Deliver Me from Nowhere focuses on Bruce Springsteen in the midst of a depressive episode, struggling to create something meaningful and finite while suicidal ideation plays discordant sounds in his head. Bruce's relationship with a waitress, Faye (Odessa Young), is doomed from the start because he can't love her in the way he knows she deserves. His past is marred by his childhood desire to protect his mother, Adele (Gabby Hoffman), from his father, Douglas (Stephen Graham), whom he was desperate to receive recognition and love from. And his music career has execs and his manager, Jon Landau (Jeremy Strong), eager to help him decide his next move while he's stuck between who he was and who he's on the path to becoming.

It's a fascinating portrait of artistry and the painful, often isolating process of creating it. If there's any point of comparison for Cooper's film, it would be Love & Mercy (2014), Bill Pohlad's film centered around Beach Boy Brian Wilson's attempts to complete the album Smile in the aftermath of a nervous breakdown while dealing with schizophrenia. Is it any wonder why the film is struggling to break out? Biopics focused on musicians have become a genre unto themselves, complete with their own agreed-upon conventions, stylistic choices, and narrative beats. While Ray (2004) and Walk the Line (2005) served as the foundation and formula for musical biopics, the success of Straight Outta Compton (2015) and Bohemian Rhapsody (2018) subsequently proved to studios that they could be major blockbusters as well.

Over the past decade, we've witnessed the pinnacle and nadir of what this genre has to offer, often involving the cramming of an individual's entire life into a 3-hour runtime, while actors attempt to cover or lip-synch their greatest hits with varying levels of authenticity. The reason why "Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story" (2007) has held a firm grip on 21st-century satirical films is evident as soon as the first trailer for a new biopic about a popular musical artist hits, as it often hits the mark spot-on. Most biopics about musicians are a pastiche, formulaic, and even when highly entertaining, end up being less informative than a Wikipedia entry. They're a series of snapshots over changing decades and aesthetics, preceded by some variation of "Dewey Cox has to think about his whole life before he plays."

"Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere," however, is not that film. While marketing for the feature has focused on Springsteen giving a concert performance, as seen in the trailers, film stills, and on the posters, the concert aspect of the movie only accounts for a few minutes of the film's opening act. Cooper flat-out rejects delivering a flashy, nostalgic vision of the '80s, complete with all of Springsteen's greatest hits, to the point where White's Springsteen catches the opening notes of "Hungry Heart" on the car radio and turns it off in disgust. In fact, the only moment in the film that straddles Cox is when Bruce and the E Street Band first record "Born in the U.S.A." But even that moment of dawning realization, "hey, I think we’ve got something here," from the sound technicians is quickly met with frustration from Springsteen who knows it doesn't fit with what he wants Nebraska to capture.

What Cooper delivers is a deconstruction of the mythology of the Boss. Rather than seeking to tell Springsteen's story in larger-than-life episodes, complete with cameos from a who's who of musical greats portrayed by various character actors, Deliver Me from Nowhere is focused on the creation of a singular album and one point in the life of Bruce Springsteen as he tries to reckon with his childhood spent in the presence of his mentally-ill, abusive father, and the angry broken pieces of America he feels connected to. These jagged spirits are what define Cooper's filmography—from "Crazy Heart" (2009) to "Out of the Furnace" (2013), "Black Mass" (2015), "Hostiles" (2017), "Antlers" (2021), and "The Pale Blue Eye" (2022), each deconstructing a genre—the redemption drama, the crime saga, the gangster movie, the western, the horror movie, and the detective story—and reframing them through the lens of American hardship, of the ghosts of the past set loose within each film's present events. He is, in my eyes, one of the most quintessential American filmmakers of his generation and there's a quality he has as a filmmaker that is not unlike Arthur Penn when it comes to deconstructing archetypes and focusing on characters who don't quite have a sense of self but are haunted by a past they can't reconcile with and a future they can't fully imagine.

It only makes sense that Cooper should bring meaning to one of the most quintessential American musical artists in the form of a stripped-down, character study that isn't about the hardships of drug abuse, fame, fortune, stalkers, or the break-up of a band but about the hardship of being alone in a room with a head full of ghosts and an empty page. Battling ghosts means confronting death, and throughout Deliver Me from Nowhere, there are long shots of Springsteen staring at elderly men. Yes, they remind him of his father. But they also remind him of himself, of what he will one day be, and it both frightens and motivates him to the point where he feels he must create something lasting and defining in his lifetime or take his own life. Of course, as the film showcases, the completion of the album wasn't a cure for his depression but only the first step towards realizing that he needed continual therapy and to reconcile and forgive his father.

The film's final message, a post-script reading that Bruce has continued to deal with depression throughout his life but never without help or hope is sincere in a way that some may find treacly. But it feels poignant and necessary in this age to be confronted with the fact that one of the defining icons of masculinity in America—born well before such emotional openness was taken seriously—is still alive because he sought help in fighting his ghosts and understood that the exorcism he needed is an ongoing journey much in the same way it is for America.

For many people, that's not